Voices

When I was six years old, my grandmother taught me to knit. She cast on, got a few rows going, and showed me how to loop the wool around the needles to make stitches. For the next few hours, I sat by her side, intent upon creating something where there had once been nothing. As the grown ups around me switched from tea to whiskey, or whatever it was they drank, each time I lost a stitch I passed this wonky scrap of knitting to her so that she could do her magic and put it right again. My misshapen piece of knitting, full of holes didn’t discourage me, I just kept going. Dogged. The perfectionist in me had not yet emerged.

My grandmother knew a thing or two about creativity. She painted and drew. She played the guitar. She learnt the harp, which loomed grand in the corner of the sitting room, and accompanied herself singing at the piano. There was the era of the violin, then that of the viola. For a few years the mournful strains of the cello would come through the floorboards. In her youth she had trained as an actress. She painted on glass, she painted portraits, still lifes and abstracts. She used oils paints, water colours, oil pastels. She made mosaics, embroidered silks, crotcheted several blankets, made patchwork quilts, wrote memoirs, short stories, and good ones at that. In her eighties she made sculptures out of springs, corkscrews, bits of string and spanners - dancing sculptures which invited a smile. She continued making and writing right up until a couple of weeks before she died in her nineties.

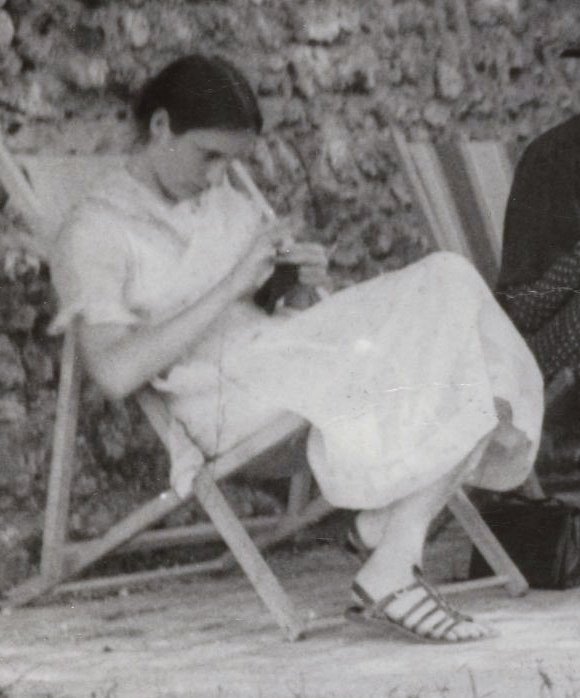

My grandmother Angelica Garnett making something as a girl

When I was in my forties, at a time when I itched to be creative, when I wanted to write, but felt blocked by the critical voices in my head - not that I yet recognised them for what they were - my grandmother gave me some advice. Are you sitting on the edge of your seat to know what this supremely creative woman said?

”Set aside some regular time where you allow yourself to make anything you want. Let yourself experiment. Don’t spoil things by expecting them to be perfect.”

Nothing new, you may think. But sometimes how much we take wise advice depends on who delivers it. It might just take years for the message to sink in.

I’m sure my grandmother knew all about the critical voices which tend to rear up the minute we start to make something. Her own parents were recognised artists, and she had to find her way out of their shadow. I know she was reduced to tears by her professor at art school. I expect she told herself at times that she was a dilettante, not serious enough, that she was flitting from one thing to another like a butterfly.

For despite growing up in a world of artists, she, like you, like me, was surrounded by the extended culture which values paintings more than quilts, yet which reveres the functional over the frivolous. For something to have worth, it must be a “success.” To be a success it must make money or be published or recognised. Our industrialised, patriarchal culture values efficiency, the serious, the professional, and that which it can measure. What’s the remedy for this crippling harshness which intimidates the creativity in us?

Let’s think about butterflies for a moment, about how freely they pollinate the flowers. Maybe we could learn something from their light touch. Think about how they melted from caterpillar to soup, went from soup to chrysalis. Think too how hard they had to work in order to emerge as butterflies.

My grandmother knew well the pleasure of getting lost in an activity which stretches one, but is just within reach of one’s capabilities. She knew that when we learn something new, initially we are better able to imagine the thing we want to do than we are capable of actually doing it. I am certain she was familiar with the tyrannical voice which says, “this is hopeless, no good, you will never manage this, just leave it to the experts.” What she also knew from experience, was that voice probably won’t go away, but the thing to do, is to keep on with the making. After a few rows of knitting, you might be too absorbed to let that voice get in your way.

It may help to remember that the inner critic has a lot to live up to. It is here to protect us from the punishing, relentless culture that drives us, that measures our worth by our productivity. My approach to that voice now is to say, “darling you don’t look very relaxed. What do you need? Chicken soup? How about an eye mask or a blanket? Why don’t you just make yourself comfortable on that sofa while I continue to bash away at my keyboard, to write my memoir, paint this picture, write that song, create my business…” You fill in the blank.

It’s the sort of thing a loving, creative grandmother might say.